Scott Prior: Illuminations

March 18 – May 29, 2021

Scott Prior: Illuminations features over 35 paintings and drawings by contemporary artist Scott Prior. Spanning five decades of Prior’s artistic career, the exhibition features the artist’s work in genres of portraiture, still life, and landscape, including new work and scenes of Cape Cod. Prior’s realistic paintings are characterized by fine detail, striking colors, and compellingly arranged compositions. His virtuoso artworks capture the beauty of everyday settings and moments, with an emphasis on the illuminating effects of light.

Curated by Cahoon Museum Director, Sarah Johnson, PhD, Scott Prior: Illuminations draws artworks from the permanent collections of the Cahoon Museum of American Art, deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, New Britain Museum of Art, Fidelity Investments, Wellington Management, and 10 private collections.

Sponsored by a Trustee of the Cahoon Museum of American Art

© Joanna Fink 2021

Every artist has their own particular origin story. Scott Prior’s began with a scientist’s sense of detached observation colliding with an emotional response to the beauty of the world. It is rooted in a uniquely New England experience of changing seasons, quirky landscapes, coastal and inland light, the old butting up against the new, nature tussling with the human-made and the ironies that this encounter reveals. It stems from Prior’s impulse to want to encapsulate in images the grander notions of beauty and spirituality as evidenced in everyday experiences.

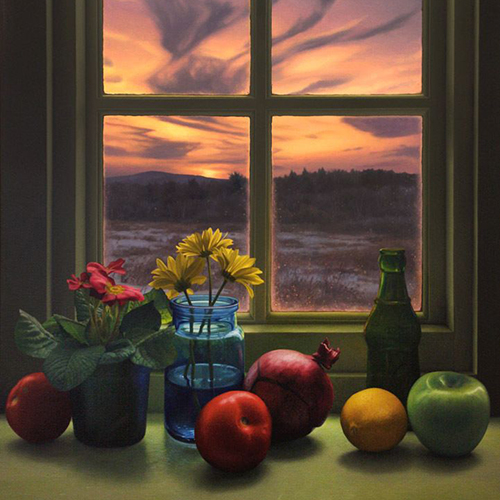

Originally interested in pursuing a career in astronomy, Prior recalls a moment as a teenager when he encountered a sunset at the end of a wayward bicycle ride. Science told him that the colors were the result of light interacting with atmospheric particles, but that didn’t explain his response to the beauty of the display. That fleeting natural phenomenon drove Prior to want to “capture and contain” the image. Perhaps art could provide another avenue to inquiry and understanding.

In that light, it makes sense that Prior pursued realism in his work. It suited what he was after. The observed world has always been the starting point, although his approach to it has evolved over his decades-long career. Prior’s combination of direct observation, photography and, later on, digital manipulation all play a role in producing the final works.

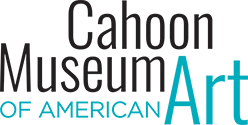

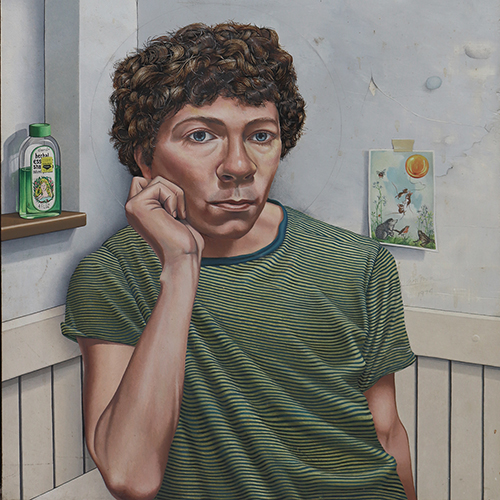

Two self-portraits from 1974 make an interesting comparison regarding the back-and-forth between observation and interpretation that became fundamental to Prior’s work. One self-portrait is rendered in graphite on paper and the other is oil on panel. For the work on paper, Prior looked directly into a mirror and the image conveys the ease of the artist’s hand, capturing the casual tilt of his glasses, the shadow-play across his face. It is an earnest self-examination, larger than life-sized and yet intimate.

The oil portrait was, instead, based on two different photographs, not relying on that same process of direct self-reflection. Melding two disparate images, this self-portrait becomes a constructed image, one that is flattened, distorted and quite “un-photographic,” in spite of the sources. While both portraits show the artist’s hand nestled against his jaw, the drawing feels natural while in the oil, as Prior has said, he seems to be “holding a mask in front of his face.” In this case photography has served, ironically, as a process of moving away from realistic portrayal, towards a different kind of truth.

Early works such as “Spherical Objects” (1975), exemplifies Prior’s surrealist leanings at the time, with meticulously rendered items from everyday life juxtaposed with strange objects that stem from the artist’s imagination. Gravity defying orbs of no clear determination co-mingle with recognizable objects. The rendering is realistic, yet the space is compressed. The details are painstaking yet there is an uneasy coexistence.

Prior was looking intently at Northern Renaissance painting in those early years. The term “realism of particulars” is often applied to the art of that time and place. Compositions were chock full of minute details of fabric, jewels, flowers, everyday objects and the like. How it all fit together was subservient to the glory of each form. “Spherical Objects” echoes this practice in its vacuum-packed realism.

Prior has attested to his obsession with spheres at that time, and they have continued to appear in his work throughout his career. In later years, the shape pops up in the form of rubber balls placed on lawns or floating in pools of water. (When Prior’s children were younger, trips to the supermarket often resulted in one more ball being brought home. They would accumulate around the property and, of course, make their way into Prior’s paintings.) “Floating Ball in Autumn” (1996) portrays the abandoned toy in a pool of water, the scene bathed in golden light. The human-made object is an alien presence in this otherwise natural setting. Spheres, of course, touch upon Prior’s origins as an astronomer, and this image can be viewed as the celestial coming to nest in the earthly.

Early in his career, Prior came under the influence of the artist Gregory Gillespie (1936-2000), whom he met in 1973, and who became a friend and mentor in the area of Northampton, MA, where Prior was living and where Gillespie had recently settled. (Prior had seen Gillespie’s work in New York City a couple of years earlier, felt a kinship, and couldn’t believe his luck when he found Gillespie to be living nearby.) The older artist’s blend of Renaissance appropriation, contemporary subject matter and surrealism bordering on phantasmagoria inspired the younger Prior to explore his own world of the real and imagined.

Using photography as a tool has been a consistent part of Prior’s process. It serves as a form of documentation, a compositional springboard, and a way to construct and re-construct memory. “Cabin in the Dunes” (2015) for example, portrays a solitary beach house at the end of a sandy path. The warm light emanating from inside the cabin is a counterpoint to the approaching dusk and dramatic play of clouds in the distance. This image is actually a composite of different photographic images collected by the artist, pieced together to create a scene that is emotionally resonant while factually implausible. Other works, such as “Abandoned Amusement Park” (2019) involve the manipulation of images to create a scene that exists only in Prior’s imagination. The amusement park is one of many themes reflecting Prior’s interest in showing attractions “off-season.” One can imagine this park as once joyful and teeming with people, but now it is dilapidated and void of human presence. Thus, we impose a constructed memory upon a constructed place.

While Gillespie was a seminal influence for Prior at an early stage in his career, a somewhat later key event was Prior’s exposure to the work of Edward Hopper, courtesy of a major exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1980. In Prior’s own words, he was “blown away” by the experience of seeing firsthand such a comprehensive view of the American master’s work. Of course, Hopper’s New England subject matter would be attractive to Prior (Hopper spent decades summering in Truro, Mass.) but even more striking to him was Hopper’s manipulation of light as a source of emotional resonance, whether stark or simmering. His figures often appeared in isolation, a state made more emphatic by the sharp contrasts of sun and shadow. Something inside Prior was ignited. This use of light, along with Hopper’s sense of melancholic solitude, prompted Prior to explore these themes in his own work.

“Bedroom in Winter” (1980) can be seen as an early nod to Hopper. Reminiscent of Hopper’s many paintings of interiors, with light streaming through large windows onto seemingly ordinary domestic scenes, “Bedroom in Winter” suggests the narrative of the unseen lives taking place within. However, while Hopper’s interiors are often simple and unadorned, Prior brings on the funk with the masterfully detailed, rumpled quilt, randomly place oddball objects and stains on the wall. While Hopper may have been whispering in his ear, Prior is responding with his own voice.

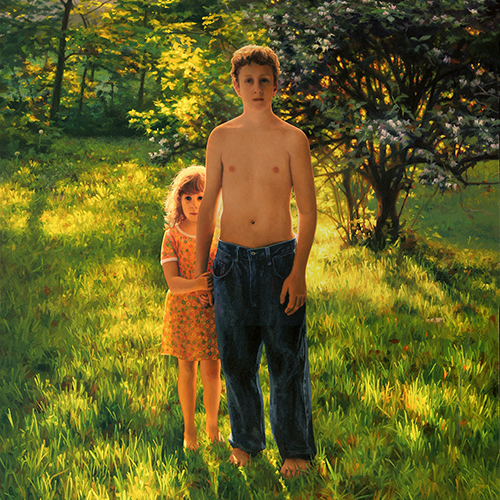

Over the course of the 1970s, Prior accomplished his goal of mastering the techniques of oil painting, but it was in the early 1980s that he achieved a more easy efficiency that allowed him to increase the scale of his works. One of the crowning pieces from this period is “Nanny and Rose” (1983), a large-scale painting that portrays his wife Nanny and dog Rose on their Northampton porch. We have been invited into an intimate domestic moment, bathrobe and all, but this is more than a casual snapshot. The background of street and neighboring houses echo the colonnades of Renaissance paintings. Nanny’s hands are clasped, resting on her lap. Her legs are crossed and her gaze is fixed in the direction of the viewer. There is a formality to the pose and a knowing look on her face. Everything we see serves a purpose. Nanny was, as it turned out, pregnant with their first child when she posed for the painting, and knowing that makes this work prophetic in retrospect.

Prior’s domestic life became his predominant subject through the 1980s and 90s as his family grew (with the birth of his three children: Max, Ezra and Nellie) and he increasingly focused on the people, interiors and surroundings from which he drew personal meaning. Paintings such as “Nellie with Carrot” (2007) capture his young children in the kind of candid moments that can fill a parent’s photo album. However, as in so much of Prior’s work, there is more going on here. A golden beam of light bounces off the girl’s hair, suggesting a halo, and her left hand takes the stance of a benediction. This small painting (only 6 ½ inches square) imbues the casual scene with grander connotations, circling back to Prior’s study of religious art of the past and his quest for the spiritual in the everyday. (It is also worth noting that Nellie was born in 1991 and was actually around 16 years old when this painting was created. Prior’s portrayals of family members did not always follow true chronology.)

Starting in his college years, Prior has spent considerable time on Cape Cod and derived inspiration from the landscape, the architecture and the qualities of light unique to the area. His first commercial success as an artist took place in Provincetown, where he would hang watercolors on a fence and sell them to passersby. Viewed as a whole, the work based on Cape Cod over the years encapsulates the arc of Prior’s development as an artist. “Provincetown Landscape” (1976) exemplifies Prior’s interest in the off-beat eccentricities often found at vacation resorts, a theme that has continued throughout his career. This commercial enterprise replete with kitschy signage, tables arranged as to defy logic and curious architectural elements shows Prior imposing his blend of surrealism and irony on this bit of Americana. Even titling the painting “landscape” humorously suggests a scene much grander than what is presented.

As Prior grew to become more focused on light effects and familiar places, his images of Cape Cod also shifted in approach. “Popcorn Stand on the Beach” (2018) carries on the theme of the off-beat commercial enterprise seen in “Provincetown Landscape” but the mood and the message seem entirely different. In the later painting the sweep of serene coastline is interrupted by the presence of the snack stand on wheels. The sky occupies a larger portion of the picture plane and the brilliant, high-keyed colors of the sunset are pitted against the stand’s electric lights. This work exemplifies Prior’s interest in the contradictions between the natural and the artificial, which plays itself out not only in his landscapes, but still lifes, as well.

Notions of nostalgia and longing are prevalent in his Cape Cod works. The recent “Cabin with Towels” (2018) depicts a modest beach house at sunset, the sky awash with color and the clouds somewhat ominous. No inhabitants are in sight, although footprints and tire marks in the sand indicate recent activity. We see an interior light shining through a window, as if they have retired for the night. The hanging towels suggest a day spent at the beach. In this painting Prior captures the sweet sadness of a summer day coming to an end.

In a 1912 essay dedicated to advice for the aspiring poet, Ezra Pound asserted that “the natural object is always the adequate symbol.” In other words, objects can speak for themselves without being weighed down with abstractions. “Sink at Sunrise” (1998) is an exercise in visual simplicity. An old-fashioned sink, plastic cups, toothbrushes (five – one for each family member) and a bar of soap are “adequate” to speak of Prior’s contentment with domestic life. He understands that poetry can lie in the most humble, ordinary of objects. Prior’s images do not extrapolate, nor preach, nor have pretense beyond what he chooses to show the viewer. The objects, people and places stand on their own as given.

The scientific explanation of our visual experience of the world boils down to light as it interacts with the objects it encounters. Scott Prior the erstwhile scientist understands that source and recognizes it as a point of departure for using that visual experience to search for deeper truths. Light is nourishing, evocative, penetrating, revelatory. The term “illuminations” can refer to images that accompanied early manuscripts, providing reference points to the given narrative. It can also refer to moments of clarity, of true understanding. It can be what nature provides, or what happens when you flick on the switch. Prior’s work encompasses all these meanings. The accrual of individual, illuminated moments weave together to form the story of Prior’s lived experience, told in the first person, plain and simple.

-Joanna Fink, art historian, curator and director of the Alpha Gallery in Boston, which has represented Scott Prior’s work since 1973.