Edward Curtis: Shadow Catcher

August 1 – December 22, 2020

This exhibition features a selection of early 20th century photographic images from Edward Curtis’ renowned body of work, The North American Indian, one of the most significant records of Native American culture ever produced.

Sponsored by an Anonymous Trustee

With additional support from Robert Paul Properties

The Cahoon Museum of American Art is situated on the peninsula of Cape Cod, the Nauset and Wampanoag (Wôpanâak) homeland. We pay respect to Nauset and Wampanoag peoples – past, present, and future –and their continuing presence in the homeland.

Edward Curtis: Shadow Catcher is curated by Sarah Johnson, PhD, Director of the Cahoon Museum of American Art

The artworks generously loaned to this exhibition are from a Private Collection.

Mia Valley of Valley Fine Art, Aspen, Colorado provided research for select content.

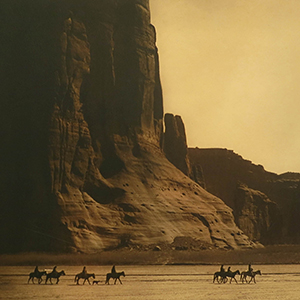

Edward Curtis: Shadow Catcher features 32 images created by legendary American photographer, Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952) from his monumental project, The North American Indian.

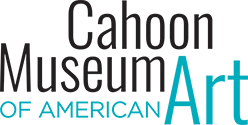

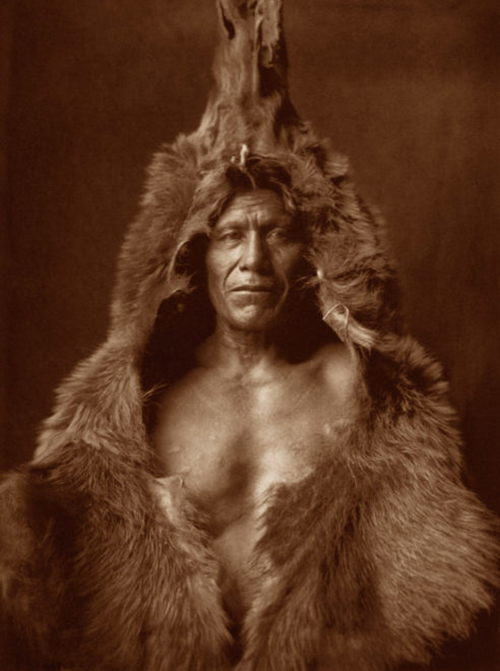

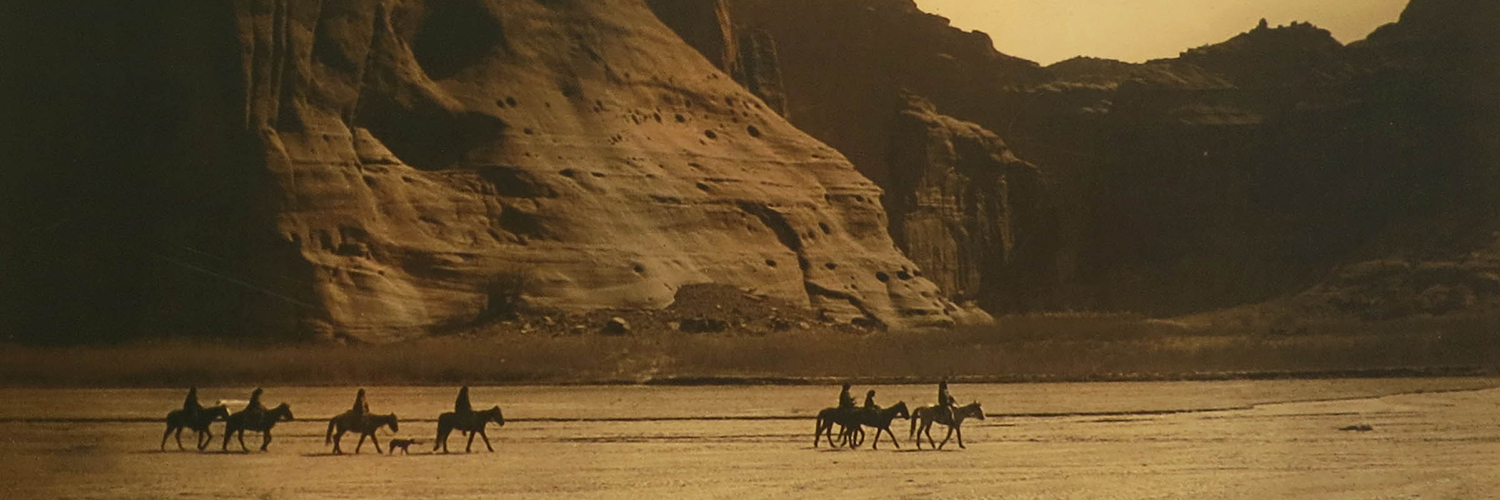

Beginning in the early 20th century and continuing over the next thirty years, Edward Curtis, or the “Shadow Catcher” as he was later called by some Native American tribes, traveled throughout the lands west of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers to document traditions and cultures of Native American peoples, a project unequaled in the history of photography. Curtis took over 40,000 images and recorded rare ethnographic information from over eighty Native American tribal groups, ranging from the Inuit people of the far north to the Hopi people of the Southwest. He captured the likenesses of many important and well-known Native Americans, including Geronimo, Chief Joseph, Red Cloud, Medicine Crow.

In 1906, the entrepreneur and banker J.P. Morgan decided to help finance his venture. With $75,000 in funding to cover travel and photographic expenses, Curtis was able to devote himself full time to the project. Morgan and Curtis planned to publish Curtis’ ethnographic text and images as a twenty-volume set titled The North American Indian. One of Curtis’ major goals was to record as much of the peoples’ way of traditional life as possible, including mythology and history, ceremonies and beliefs, foodways, language, music, dwellings, clothing, games, tools and physical surroundings as well as biographical sketches of tribal leaders. With urgency, Curtis said, “the information that is to be gathered… respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost.”

Morgan and Curtis decided that each leather-bound gold-embossed volume would be illustrated with 75 photogravures made from Curtis’ glass plate negatives and would be accompanied by an unbound portfolio of large photogravures. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had become a family friend of Curtis when he photographed the President’s family a few years earlier, agreed to write the forward. In return for his support, Morgan was to receive 25 sets of The North American Indian plus 500 original photographs.

Publication would be funded by selling subscriptions at $3,000 per set, with 500 sets to be printed.

In reality, the undertaking was in financial trouble throughout the entire 24-year period between 1906 and 1930. Curtis constantly tried to keep his project afloat by maintaining a grueling lecture and exhibition schedule and selling original photographs.

Not only were the logistical and financial responsibilities of the fieldwork constant, the expenses related to publishing the books were staggering. The craftsmanship and materials Curtis insisted on using were of the highest quality. He used the difficult and expensive process of photogravure for both the volume and portfolio prints. The process allowed Curtis to make prints of great subtlety and beauty, but the resulting expense of each set led to a shortfall in sales. Of the projected five hundred sets, less than three hundred were actually produced.

Such a massive project was almost incomprehensible. In addition to the constant struggle for financing, Curtis required the cooperation of the weather, vehicles, mechanical equipment, skilled technicians, scholars and researchers and the Native tribes. He dispatched assistants to make tribal visits months in advance. Curtis would travel by horseback or horse-drawn wagon over rough roads and paths to visit the tribes in their home territory. Once onsite, Curtis would interview the people and then photograph them either outside or inside his studio tent.

Curtis was praised for his photographic talents, he received some criticism from ethnologists largely because he lacked an academic background and because the photographs were artistically staged to some degree. Curtis considered himself both an ethnologist and an artist working in the Pictorialist photographic tradition. While Curtis used an artist’s eye for composition and beauty, his presentation of his subjects was an homage to their earlier ways of life, which he believed was in danger of being lost.

Contemporary ethnologists take issue that Curtis posed his sitters and eliminated evidence of modern life, thus creating an idealized image of Native peoples located in the past and untouched by Western society, rather than as contemporary peoples, alive, surviving, and adapting to changes. Some contemporary scholars note that Curtis’ work did little to raise consciousness about the conditions of Native American life in early 20th century America and that the representation of indigenous peoples as a vestige of the past, irreconcilable with the forces of modernity, continues to impact Native Americans.

Many of the Native Americans that Curtis photographed called him “Shadow Catcher.” In his effort to capture the spirit of the time before it faded away, the images he created were far more powerful than shadows. The men, women, and children in The North American Indian seem as alive to us today as they did when Curtis took their pictures in the early 20th century. Biographer Laurie Lawlor explains that, “Curtis respected the Native Americans he encountered and was willing to learn about their culture, religion, and way of life. In return the Native Americans respected and trusted him. When judged by the standards of his time, Curtis was far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance, and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking.”

Despite Curtis’ monumental accomplishment, The North American Indian did not receive the attention and acclaim its creators had anticipated. At $3,000, very few individuals could afford the set. Nearly two centuries of violent conflict between European settlers and Native American tribes were nearing an end and the surge of interest in Native Americans that characterized the turn of the century was on the wane. By the time Edward Curtis died in 1952, The North American Indian had been all but forgotten.

In recent decades, interest in Curtis revived and people began to appreciate the value of Curtis’ achievement. Many Curtis biographies and compilations of images have been published and restrikes from the original plates are still being sold. In the end, Curtis succeeded in creating a powerful record of human presence, and his life’s work documents an important part of American culture and history that should be remembered.

Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952) was born on a farm in rural Wisconsin. His father, a minister, farmer, and Civil War veteran moved his wife and four children to Minnesota for better opportunities. Curtis left school in the sixth grade and became interested in photography; he built his own camera and learned to process prints.

At the age of 17, Curtis became an apprentice photographer in St. Paul, Minnesota. When his family moved again to Seattle, Washington, he purchased a new camera and became a partner in a photographic portrait studio with Thomas Guptill. Their business, Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers, catered to local businessmen and their families. Curtis married a family friend, Clara Phillips, and they soon had four children.

By 1896, Curtis had established himself as Seattle’s foremost studio photographer, and his success gave him a level of financial freedom that allowed him to spend time away from the studio. He experimented with photographing the area’s spectacular mountain and ocean scenery, and this led him to encounter small pockets of Native Americans who still maintained some of their traditional lifeways. By 1898, Curtis had begun receiving recognition from the photographic community and the general public for his portraits of Native Americans.

The same year, a chance event significantly altered the course of his life. While on a mountaineering trip, Curtis rescued a lost party of climbers on Mount Rainier that included several prominent people nationally recognized for their work in conservation, indigenous ethnography, and publishing, including George Bird Grinnell.

Grinnell invited Curtis to join an important scientific expedition in 1899 which gave him his first real grounding in the discipline and rigors of the scientific method. He practiced and developed his photographic skills and project methodology that would guide his lifetime of work. The next year, Curtis joined Grinnell to witness the Sun Dance ceremony in Montana. Grinnell, known as the Father of the Blackfoot, had established a position of knowledge and trust with the Blackfoot and Piegan peoples that opened new doors for Curtis. It was this access to closely held native rituals and spiritual beliefs that profoundly changed Curtis’ life. He resolved to begin documenting the life of this country’s indigenous people: their myths, songs, history, language and, especially, their faces, all of it rapidly disappearing.

Curtis’ wife Clara and the couple’s three older children often accompanied Curtis on the early trips for The North American Indian project, but the family soon grew tired of the hard work and disruptive travel, often to remote places. Nearly all the family’s resources were depleted for the project. In 1916, Clara filed for divorce and was awarded the photographic studio and all its contents. Curtis encountered every imaginable difficulty in the following years. At the time of the divorce, Curtis had published only eleven of the twenty volumes. Broke, exhausted, and without a studio, he halted work on The North American Indian in 1919.

The intensity with which Curtis pursued his dream consumed thirty years of his life, and eventually cost him everything, including his health, family and creative and financial control of The North American Indian. The Great Depression ultimately brought an end to Curtis’ dream, forcing him to declare bankruptcy. Following his recovery two years later, he spent the last twenty years of his life in Los Angeles with his daughter Beth. He died in 1952, largely unknown and penniless.

Curtis’ project was unique for its time, and the enduring legacy of The North American Indian remains, a monumental record of the humanity and strength of Native Americans, at a time when their way of life was under constant threat.

The Private Collector whose artworks are featured in this exhibition began a passionate collecting journey with works by Edward S. Curtis decades ago. The Collector first encountered Curtis’ photogravure, Jicarilla Maiden, in a shop in Colorado. Captivated by the girl’s presence in the image, the Collector sought out more opportunities to acquire Edward Curtis images over the decades. The Collector remains inspired by Curtis’ artistry, especially with visual compositions, as well as the poignant moment in American history that Curtis reflected.

While focusing on acquiring photogravures produced by Curtis during his lifetime for The North American Indian, from time to time the Collector purchased restrikes (reproduction images from Curtis’ original plates) because of their availability and an attraction to the particular image.

Many of Curtis’ vintage photogravure plates have been used to restrike or reprint images since the 1960s and various individuals and businesses have controlled the existing original photogravure printing plates.

Curtis experimented with a number of different photographic techniques and processes including platinum prints, gelatin silver prints, goldtones, cyanotypes, and hand-colored prints.

The vast majority of Edward Curtis’ prints were printed as vintage photogravures, and virtually all of them were produced for The North American Indian. Curtis used two standard sizes: 5 x 7 and 12 x 16 inches. He favored three types of hand-made papers: Japanese Vellum, Dutch ‘Van Gelder’, and Japanese Tissue, also known as India Proof Paper.

Photogravure is a printmaking process that involves transferring a photographic image onto a copper printing plate. The plate is then etched and used to make an ink-based photographic print. A dampened sheet of paper is placed on top of the inked plate, which is then run through an etching press. This process was popular with Pictorialist photographers at the end of the 19th century who wanted to raise the status of photography to fine art. The vintage photogravure process produced a finely nuanced continuous tone image.

Chief Joseph (1840–1904) is widely considered to be one of the most important tribal leaders of the 19th century. He was a leader of the Nez Percé tribe during the most tumultuous period in their history, when they were forcibly removed by the United States government from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley of northeastern Oregon onto a significantly reduced reservation in the Idaho Territory.

In 1877, after two years of violent encounters with white settlers, a group of Native Americans – including Joseph’s band and an allied band of the Palouse tribe – resisted removal. They fled the United States in an attempt to reach political asylum alongside the Lakota people, who had sought refuge in Canada under the leadership of Sitting Bull.

During the fighting retreat known as the Nez Percé War, the skill with which the Nez Percé fought and the manner in which they conducted themselves in the face of incredible adversity earned them widespread admiration from their military opponents and the American public and coverage of the war in U.S. newspapers led to popular recognition of Chief Joseph and the Nez Percé.

In 1877, Joseph’s band was cornered in northern Montana Territory near the Canadian border. Unable to fight any longer, Chief Joseph surrendered in order to save the lives of their women and children and with the understanding that he and his people would be allowed to return to the reservation in Idaho. He proclaimed the words that became famous, “I will fight no more forever…” Joseph was instead transported between various forts and reservations on the southern Great Plains before being moved to the Colville Indian Reservation in the state of Washington, where he died in 1904. Chief Joseph remains renown as a humanitarian and peacemaker for his passionate, principled resistance to his tribe’s forced removal.

Chief Joseph became close friends with Edward Curtis and this friendship was critical to Curtis’ later success in gaining the trust of numerous other tribes.

Joseph’s pride, nobility and tragic experiences that he and his people suffered are all evident on his face in Curtis’ image.

Curtis hired several employees to help him with The North American Indian. Former journalist, William E. Myers assisted with writing and recording Native languages, and anthropologist Frederick Webb Hodge was hired to edit the entire series. Bill Phillips, a graduate of the University of Washington, helped with logistics and fieldwork, as did Native American, Alexander Upshaw, who assisted Curtis collect material about the Northern Plains tribes.

Alexander B. Upshaw, son of an Apsaroke chief, was educated at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, graduating in 1897. After resigning his teaching position in Genoa, Nebraska, Upshaw returned to the Apsaroke-Crow Reservation in Montana and worked as a translator and tribal advocate.

In 1905, Upshaw began his collaboration with Edward S. Curtis as an interpreter and researcher, providing Curtis with remarkable and unfettered access to the Northern Plains tribes. Their ethnographic investigations included an expedition to the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn with surviving Crow and Sioux eyewitnesses, resulting in a dramatically different scholarly analysis of the battle from the approved governmental narrative. The conclusion of their inquiry was omitted from The North American Indian due to political pressure.