Daguerreotype Masterworks from the Dawn of Photography

September 6 – October 30

Opening Reception: September 13, 4:30 – 6:00pm

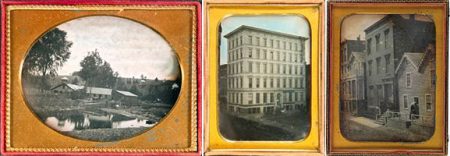

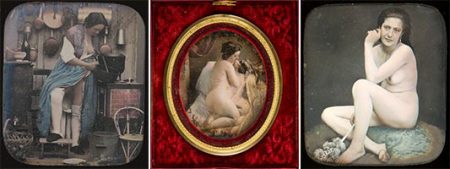

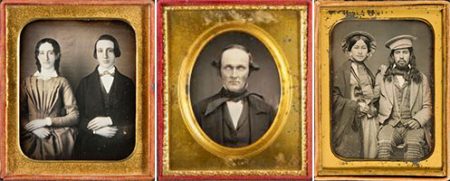

This exhibition is a comprehensive survey celebrating the art of the daguerreotype, Through the Looking Glass features important examples from America, France, England, and the Middle East. The nearly 150 plates include both cased examples and larger framed plates. All the major collecting genres of daguerreotypes: landscapes, architectural studies, occupationals, erotic stereoviews, post-mortems, and of course portraiture are represented by superb, often surprising examples.

Through the Looking Glass proudly supported by:

This exhibition is a comprehensive survey celebrating the art of the daguerreotype, Through the Looking Glass features important examples from America, France, England, and the Middle East. The nearly 150 plates include both cased examples and larger framed plates. All the major collecting genres of daguerreotypes: landscapes, architectural studies, occupationals, erotic stereoviews, post-mortems, and of course portraiture are represented by superb, often surprising examples.

The daguerreotype was the first successful method of photography. Created by Frenchman Louis Daguerre (1787-1851), he announced the invention to an electrified audience in Paris on August 19, 1839, at a joint meeting of the Académie des Sciences and the Académie des Beaux- Arts. A joint forum was the appropriate venue, as Louis Daguerre’s invention would prove equally revolutionary in science and technology, in social history, and in the arts. The daguerreotype process was introduced to a worldwide audience in 1839 and became widely used during the 1840s and 1850s.

The painter Samuel Morse, also known as “the American Leonardo,” attended the 1839 meeting where he was being honored for his invention of the telegraph. While in Paris, Morse learned daguerreotypy from Daguerre himself; back in New York, Morse then taught the art to interested colleagues in both the arts and sciences who would go on to open portrait studios of their own. While “daguerreotypomania” swept both France and America, it was in America that it had its greatest social (and commercial) impact, as portraiture of everyday people captured the essence of democracy.

The daguerreotype was the dominant mode of photography in France in the 1840s, but in America the daguerreian era would last through the 1850s. By the time of the Civil War it had been supplanted by the ambrotype, the tintype, and especially the albumen print from a collodion-on- glass negative, which would prevail till the turn of the century.

A daguerreotype is a highly polished silver-coated copper plate upon which an image is directly exposed, often requiring exposures lasting ten minutes or more. Each daguerreotype is a unique, one-of-a-kind object. With it’s brilliant, mirror-like surface and its ornate case, small enough to hold in the hand or carry in the pocket, the daguerreotype was suited to a vivid and intimate representation of a loved one.

This exhibition, curated from the private collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, celebrates the art of the daguerreotype on both sides of the Atlantic. All the major collecting genres of daguerreotypy – landscapes, architectural studies, occupationals, erotic stereos, post-mortems, and of course portraiture – are represented by superb, often surprising examples. The show is organized by art2art Circulating Exhibitions, LLC.

READ MORE:

Antiques and the Arts Weekly, May 5, 2015

Through the Looking Glass

The following content has been provided by art2art Circulating Exhibitions, LLC

Southworth & Hawes

Among the dozens of people whom Samuel Morse tutored in daguerreotypy in 1839-40 was an ambitious 29-year-old Boston pharmacist, Albert Sands Southworth. “You have read of the daguerreotype, an apparatus for taking views of buildings, streets, yards, and so forth,” he wrote to his sister, Nancy Southworth Hawes. “I cannot in a letter describe all the wonders of this apparatus. Suffice it to say, that I can now make a perfect picture in one hour’s time, that would take a painter weeks to draw. The picture is represented in light and shade, nicer by far than any steel engraving you ever saw.”

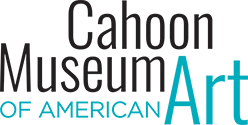

Occupational Daguerreotypes

One widely collected sub-genre of daguerreotypes is that of so-called “occupationals” in which a man is depicted with the accoutrements of his trade. (Note that female occupationals are vanishingly rare.) While French examples exist (see the Painter and the Priest), occupational daguerreotypes were largely an American phenomenon. They were likely deployed as high-end “business cards” to be displayed in shop windows, given out to preferred customers, or mailed to proud parents. Viewed collectively, they speak to a growing mid-century entrepreneurial class of craftsmen and shopkeepers who pushed the nation’s borders ever westward in self-confident pursuit of the American Dream. Particularly unusual examples are seen here, including the Clamdigger, the Lighthouse Keeper, the Barber and his Client, the Taxidermist, and the Wheelwright.

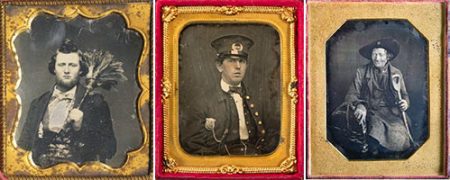

Medical and Scientific Daguerreotypes

On either side of the Atlantic, doctors were among the early adopters of the daguerreotype, and medical photography was one of its first important applications. Two months after Daguerre’s announcement, the noted Parisian doctor Alfred Donné discovered the means to make an acid-etched plate from a daguerreotype, which allowed photo-mechanical ink reproductions of a photographic image. Combining a daguerreotype camera with a microscope, Donné published the first photographs of red blood cells and is credited with the discovery of platelets.

Within a few years, leading medical journals and textbooks began publishing clinical images as reproductions after daguerreotypes, rather than from lithographs or ink drawings. Louis-Auguste Bisson’s astonishing “Portrait of a man with large facial tumor” (seen here) is a supreme example of this genre; it was likely intended for reproduction in a scientific article on facial deformities.

In New York, Samuel Morse’s first pupil in daguerreotypy was John W. Draper, the chair of NYU’s chemistry department and the founding director of the NYU School of Medicine. By experimenting with lens lengths, Draper was the first to shorten the exposure time to under a minute; this critical early breakthrough resulted in the first daguerreian portraits of subjects with their eyes open. Later he used daguerreotype reproductions for his textbook Human Physiology.

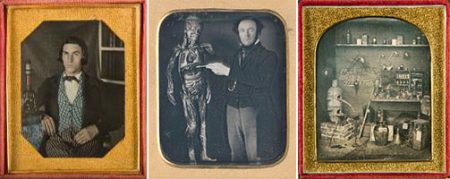

Military and Hunting Daguerreotypes

Some of the most memorable daguerreian portraits are of hunters and military men. These portraits capture their subjects at their proudest moments, and in full sartorial display, sometimes brandishing their weapons. Many soldiers had their portraits made as keepsakes for their families just before deploying to active service. Unfortunately, daguerreotype technology with its long exposure time was not able to record a battle in progress. By the time of the Civil War, photographers such as Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner had switched to the more versatile technique of the albumen print made from a collodion-on-glass negative.

Outdoor Daguerreotypes

The daguerreotype was primarily a means of studio portraiture; fewer than one in a thousand was made outdoors. One reason is that daguerreotypy was consumer-driven: it satisfied a pent-up demand for affordable portraiture. Few daguerreotypists, especially American practitioners, were motivated to create landscape images to satisfy a purely artistic impulse. A second reason for the relative paucity of outdoor views is technical: only the most skilled makers could properly account for the vagaries of outdoor lighting conditions, or the effect of temperature variations on the sensitized silver-coated copper plates.

For reasons of rarity alone, outdoor daguerreotypes have always been especially prized by collectors. But only a small percentage are objects of artistic worth. The large majority of American outdoor daguerreotypes are best understood as trophies of middle-class achievement, visual proclamations of “This is my house!” or “This is my horse and buggy!”

The outdoor daguerreotypes in this exhibition have been selected on the basis of artistic merit. Whether American, French, or Middle-Eastern, whether by known or unknown makers, they display sophisticated, sometimes radical, composition and skilled use of outdoor light.

“Blue-Plate Specials”: Solarized Daguerreotypes

Like other 19th century photographic processes, the daguerreotype was overly sensitive to ultraviolet light. A plate in which the sky was overexposed had a tendency to appear blue in the highlights, an effect known as ‘solarization’. There was considerable debate at the time whether solarization was a bug or a feature. High-end portrait studio operators like Southworth & Hawes would dismiss their low-cost, low-skilled competitors as “blue-bosom boys” because white shirt-fronts would solarize to blue in portrait sittings if the timing of the exposure was off. But to modern eyes, solarization can be a lovely, often surreal effect, especially in outdoor scenes such as those displayed here. A blue sky suggests a color photograph even without the addition of hand-tinting, though true color photography was still a half century away.

Eros: French Erotic Daguerreotypes

150 years before erotica became the “killer app” of the internet, a similar phenomenon swept through French daguerreotypy. The key technological advance was the lenticular stereoscope developed in 1849 by the Scottish scientist, Sir David Brewster. This was a hand-held device that gives the illusion of three-dimensionality when a variant pair of daguerreotype plates (a “left-eye” and a “right-eye” image) are inserted into the viewer. Unable to secure a reliable British manufacturer for his invention, Brewster engaged the Parisian instrument maker and photographer Louis Duboscq. Within months of this new technology, Duboscq and a half-dozen other enterprising French photographers were creating stereoscopic nudes by the hundreds, in response to exponentially increasing customer demand. Most of these stereo daguerreotypes were clumsily posed, amateurishly hand-tinted, and were intended for prurient interest only. But the best of the genre (as shown here) are gorgeously colored and artfully composed and lit, in the manner of the Neoclassical painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.

Thanatos: Post-Mortem Daguerreotypes

In present-day first-world society, death and dying have been medicalized. A dying person is quarantined from the living and is ministered by medical professionals. But in Victorian society, death was viewed as a natural and integrated part of life, and daguerreotypists made their services available to record this ultimate rite of passage for posterity. Southworth & Hawes advertised these solemn keepsakes in suitably sensitive prose:

“We make miniatures of children and adults instantly and of Deceased Persons either at our rooms or at private residences. We take great pains to have miniatures of Deceased persons agreeable and satisfactory, and they are often so natural as to seem, even to Artists, in a quiet sleep.”

It is worth pondering that among the lower classes, a post-mortem was often the only portrait made over the course of a lifetime.

The practice of post-mortem photography outlived the daguerreian era by several generations, finally tapering off in America by the 1930s.

Daguerreian Portraiture

“From today, painting is dead.”– painter Paul Delaroche, in 1839, upon seeing the first daguerreotypes

While Delaroche’s famous prediction proved overly dramatic, it can be argued that the daguerreotype liberated painting from its centuries-old function of representational portraiture, and, in so doing, hastened the development of modern art.

Certainly, the daguerreotype democratized portraiture, which was no longer the exclusive birthright of the wealthy. The daguerreian era is the first generation for which we can look back and know how every nook and cranny of society looked and dressed. In America especially, daguerreotype studios sprouted along the main thoroughfares of every city. Some pricey studios, such as Mathew Brady’s in New York and Southworth and Hawes’s in Boston, catered to the upper crust, but low-cost competitors were accessible to the middle and working classes. Even rural Americans in remote locations could have their likenesses taken a few times a year when their villages were visited by mobile daguerreotype studios, which were self-contained trailers pulled by a team of horses or oxen.

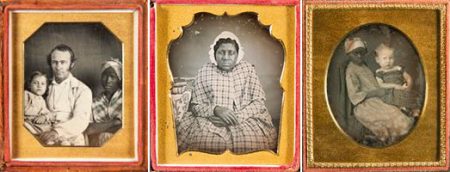

Picturing Slavery

Daguerreotypes produced in the American South provide a poignant window into the horrific institution of slavery. Their varying meanings have been recently deconstructed by scholars Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer in Envisioning Emancipation: “The inclusion of a slave in these portraits of white children and families signaled the family’s wealth and, like fancy clothes or jewelry, was a mark of status. The presence of a black nurse also reflected the sentimentality slaveholders projected onto the black women who worked in their homes: the stereotypical ‘mammy’, the stern but loving caretaker and devoted slave/servant, presented as a favored doll or pet, as a record of a treasured possession. A viewer could see that the black subject was well dressed, suggesting that she was also well cared for – a counterweight to abolitionist arguments.”